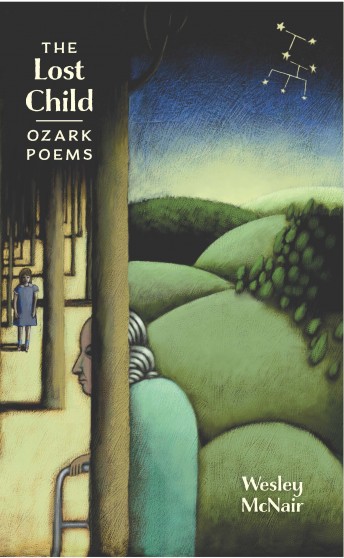

The Lost Child - Ozark Poems. Wesley McNair. David R. Godine Publisher. Jaffrey, New Hampshire. 2014.

Winner of the 2015 PEN New England Award for Literary Excellence in Poetry

Wesley McNair's opus is both tribute and lament. These poems sprawl across every sense you have with operatic flourish. This is narrative poetry writ large and Today's book of poetry can't get enough.

McNair's mother is reaching the end of her mortal coil and it isn't pretty. The scenes these poems illuminate are often small in scale but McNair is epic in scope, he sees the whole picture as it is happening and puts the essentials down in such a way that we cannot resist moving forward, the poems themselves compel us.

When She Wouldn't

When her recorded voice on the phone

said who she was again and again to the piles

of newspapers and magazines and the clothes

in the chairs and the bags of unopened mail

and garbage and piles of unwashed dishes.

When she could no longer walk

through the stench of it, in her don't-need-nobody-

to-help me way of walking, with her head

bent down to her knees as if she were searching

for a dime that had rolled into a crack

on the floor, though it was impossible to see

the floor. When the pain in her foot she disclosed

to no one was so bad she could not stand

at her refrigerator packed with food and sniff

to find what was edible. When she could hardly

even sit as she loved to sit, all night

on the toilet, with the old rinsed diapers

hanging nearby on the curtainless bar

of the shower stall, and the shoes lined u

in the tub, falling asleep and waking up

while she cut out newspaper clippings

and listened to the late-night talk

on her crackling radio about alien landings

and why the government had denied them.

When she drew the soapy rag across the agonizing

ache of her foot trying over and over to wash

the black from her big toe and could not

because it was gangrene.

When at last they came to carry my mother

out of the wilderness of that house

and she lay thin and frail and disoriented

between bouts of tests and x-rays,

and I came to find her in the white bed

of her white room among nurses who brushed

her hair while she looked up at them and smiled

with her yellow upper plate that seemed to hold

her face together, dazed and disbelieving,

as if she were in heaven,

then turned, still smiling, to the door

where her stout, bestroked younger brother

teetered into the room on his cane, all the way

from Missouri with her elderly sister

and her bald-headed baby brother,

whom she despised. When he smiled back

and dipped his bald head down to kiss her,

and her sister and her other brother hugged her

with serious expressions, and her childish

astonishment slowly changed

to suspicion and the old wildness returned

to her eye because she began to see

this was not what she wanted at all,

I sitting down by her good ear holding her hand

to talk to her about going into the home

that was not her home, her baby brother winking,

the others nodding and saying, Listen to Wesley.

When it became clear to her that we were not

her people, the ones she had left behind

in her house, on the radio, in the newspaper

clippings, in the bags of unopened mail,

in her mind, and she turned her face away

so I could see the print of red on her cheek

as if she had been slapped hard.

When the three of them began to implore

their older sister saying, Ruth, Ruth,

and We come out here for your own good,

and That time rolls around for all of us,

getting frustrated and mad because they meant,

but did not know they meant, themselves too.

When the gray sister, the angriest of them,

finally said through her pleated lips

and lower plate, You was always

the stubborn one, we ain't here to poison you,

turn around and say something.

When she wouldn't.

...

Epic in scope, that's the ticket. These may be small stories of almost too intimate detail but they are wonders to behold. These poems take up the whole page just like the works of Hieronymus Bosch if they were edited by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. There is a lot going on.

There is so much going on in these poems we are unsure of where to look but McNair holds his gaze and does not back down from his mother's gangrenous toes or anything else. The Lost Child - Ozark Poems is full of tender sadness and impending doom, all of it swinging from a family tree filled with broken fruit.

Her Secret

Why her husband must spread his things over every

table, counter-top, and chair, just like his mother Ruth,

Dolly no longer asks, knowing he will only answer as if

speaking to someone in his head who's keeping track

of all the ways she misunderstands him and wants

to hear over and over that he's sick and tired,

though that's just what he is, and how, anyway,

can she resent him for that? -- so sick he has pill vials

for his bad circulation, bad heart, and nerve disorder

scattered around the kitchen sink, so tired

after staying up all night at his computer feeding

medication to the stinging in his legs, he crashes

for one whole day into the next. "Thurman?" she asks,

coming home from work to find him lying on their bed

in his underpants, still as the dead, his radio on

to tape the talk shows he's missing, and then the old

thought that he really is dead comes into her mind

all over again, so strong this time she can't

get rid of it, even after she sees him with her

own eyes just above the partition in the kitchen

making coffee in the way he's invented, boiling

his grounds, them putting in more grounds and a raw

egg, his bald head going back and forth under

the fluorescent light like the image of his continuous

obsession, which she can't escape and can never enter,

though now it's her own obsession that troubles her.

Stupid is her word for it, the same word he always

uses for the crazy things she gets into her head,

and it was stupid, still thinking Thurman was dead

though he was right there in front of her, and then,

when she tries to make herself stop, her heart stops

pounding until she can hardly breathe. "It is nothing

more than simple anger," the pastor tells Dolly

after the service at the church in Seymour

she attends each Sunday with the other women

who live nearby, and he recalls with a frown

of disappointment the anger he discovered in her heart

during their talk a year ago. How, she wonders,

could she have forgotten that after she wiped away

her tears in the earlier conversation about Thurman's

leaving things he wouldn't let her touch on every

surface in the house, even the couch and chairs,

the pastor made her see the malice she had carried

so deep inside not even she understood that all

this time she had been gradually filling the spare room

and the closed-in porch with her own discards,

broken figurines, old mops and mop pails and Christmas

decorations, out of a secret revenge. "And now,"

the pastor shakes his head, "this thought about your

husband, whom you have pledged to honor, lying

in his underpants, dead, the day before your fortieth

anniversary." When Dolly returns home at last

and opens the door to find the two pairs of sneakers

next to the recliner with the ankle brace in it,

and old videos on top of the half-read magazines

and newspapers by the TV, and the bathrobe and shirts

and pants folded over the backs of chairs, she does not

feel, as she sometimes has, that she might suffocate,

but instead, a relief that Thurman hasn't risen yet.

He won't mind, she thinks, that she's used one

of his sticky notes when he has read the words

she writes on it, I still love you, meaning how sorry

she is for blaming him behind his back to the pastor,

and for the secret anger she has kept so long

in her heart, yet because, unlike most things

in that house, it is hers alone, Dolly continues

to ponder the anger and keep it, even after Thurman

takes the note from the screen of his computer

with a smile, and gets his camera out to take

the anniversary photo he takes each year for his emails

of her holding plastic flowers, irritated with her

because she never could pose right, then sitting down

among the wires and the stacks of CDs and computer

paper to photoshop it, going over and over her teeth

and eyes to whiten them and taking all the wrinkles out

of her face until she looks like an old baby. "Oh

this is nice," Dolly says when he brings the picture

to her, sitting on her small rocker in the only

uncluttered corner of the house, and she almost

means it, she has become so calm in her pondering

as she looks out the window and through the other

window of the closed-in porch, where a flock

of the migrating birds she loves linger for a time

under the roof of her feeder, and in an unaccountable

moment, lift their wings all together and fly away.

...

Pace and timing. Wesley McNair's The Lost Child - Ozark Poems is a brisk march that never lets up. McNair has a metronome inside his mechanism that seemingly never lets him down, it certainly punctuates these stories, pathos rains down like a forest falling.

McNair really does have a narrative gift unlike any other poet Today's book of poetry has been lucky enough to read. These poems have Ballad of the Sad Cafe holding up a corner of the card table.

Dancing in Tennessee

How was he to know, when his father left them

and his mother took him by the hand

to her clothes closet, screaming

because he did not understand how to behave

and because, alone and lost, she herself

did not understand how to behave,

that this was the room she led him to,

20B in the nursing home, where he sat

once more in the dim light among her slippers

and shoes, calling out to her, "Mama, Mama,"

though now she was right there

in her bed, half-deaf, eyes wide open

in her blindness, her teeth out,

breathing rapidly through her mouth?

How could he have known when she whipped him

as if she would never stop because his father

loved someone else, it was the shock

of this final unbelievable lovelessness

she was preparing him for? All gone, her years

afterward with the new man, and the house

and farm she helped build to replace

the hopes that she once had. Gone

to ruin, the house and the farm,

but never mind. And never mind

her lifelong anger, and all her failures

of the heart: this was not his mother.

Lying on her stroke side, her nose

a bony thing between her eyes that blinked

and blinked so he could see behind them

to her fear, she was a creature

whose body had failed, and he had no way

to reach except through her favorite song

he sang as a boy to lift the grief from her face,

and began now to sing, "The Tennessee Waltz,"

understanding at last that its tale of love stolen

and denied was the pure inescapable

story of her life -- his father the stolen

sweetheart she never forgave

or forgot. It didn't matter that she could not

see him beside her there or, struggling for air,

she was unable to eat or drink

or sing. He took her good hand in his

and rocked her and sang for them both,

his mother discovering once more in the tips

of her fingers what touch was like,

and he discovering too, while he sang on

and on, stealing her back from this moment

in the small, dim room where she lay dying,

and they danced and danced.

...

And now all you Tennessee Ernie Ford fans know what Today's book of poetry knows, Wesley McNair can cook. The poems in The Lost Child all come from one narrative, tied together with barbed wire and blue ribbon, like most family histories, moments of kindness remembered among the tatters of old frustrations and never fully sated dreams.

Love and those we love often bring out the sorrow.

Wesley McNair writes grand scale with a stethoscope planted firmly on the readers heart.

Wesley McNair

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Wesley McNair is the Poet Laureate of Maine. He is the author of twenty books, including ten volumes of poetry, three books of nonfiction, and several edited anthologies.. His most recent books are The Lost Child: Ozark Poems (Godine, 2014), The Words I Chose: A Memoir of Family and Poetry(CMU, 2012) and Lovers of the Lost: New & Selected Poems (Godine, 2010).McNair is the recipient of fellowships from the Fulbright and Guggenheim Foundations, a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship in literature, two Rockefeller fellowships for creative work at the Bellagio Center in Italy, two National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships for Creative Writers, and in 2006 a United States Artists Fellowship of $50,000 as one of "America's finest living artists." He was recently named as the 2015 recipient of the PEN New England Award for Poetry, for his latest collection, The Lost Child: Ozark Poems. Other honors include the Robert Frost Prize; the Jane Kenyon Award for Outstanding Book of Poetry (for Fire); the Devins Award for poetry; the Eunice Teitjens Prize from Poetry magazine; the Theodore Roethke prize from Poetry Northwest; the Pushcart Prize, and the Sarah Josepha Hale Medal for his "distinguished contribution to the world of letters."

He has received five honorary degrees for literary distinction.

Wesley McNair has twice been invited to read his poetry by the Library of Congress and has given readings at a wide range of colleges and universities. A television series aired over affiliates of PBS on Robert Frost for which he wrote the scripts received an Emmy Award. Featured on National Public Radio's Weekend Edition (Saturday and Sunday programs) and 22 times on Garrison Keillor's Writer's Almanac, his work has appeared in the Pushcart Prize Annual, two editions of The Best American Poetry, and over 60 anthologies and textbooks. He has served four times on the jury for the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry.

BLURBS

By the faculty of his attention—to people, to their talk—McNair’s compassion turns itself into art. – - Donald Hall, The Harvard Review[He is] a master craftsman with a remarkable ear.

– Maxine Kumin,Ploughshares

He has produced one of the most individual and original bodies of work by a poet of his generation.

He has produced one of the most individual and original bodies of work by a poet of his generation.

– Ruminator Review

478

DISCLAIMERS

Poems cited here are assumed to be under copyright by the poet and/or publisher. They are shown here for publicity and review purposes. For any other kind of re-use of these poems, please contact the listed publishers for permission.

We here at TBOP are technically deficient and rely on our bashful Milo to fix everything. We received notice from Google that we were using "cookies"

and that for our readers in Europe there had to be notification of the use of those "cookies. Please be aware that TBOP may employ the use of some "cookies" (whatever they are) and you should take that into consideration.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.