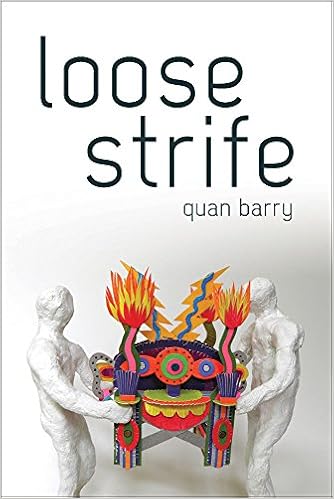

Loose Strife. Quan Barry. University of Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh, Pa. 2015.

Quan Barry is utterly magic.

Not that smarmy bright light "and for my next trick..." magic. Barry is magical because she instantly transports the reader to a new reality. We recognize where we are at all times when reading Barry but also realize it has never looked quite so real in quite this way.

Whether she is writing about the killing fields of Cambodia or the tunnels of Cu Chi, and we have all heard the horrors, the reader is whisked to a reality previously invisible and unavailable.

Barry pulls off the remarkable feat of being clear like crystal but hard as diamond, hard as nails, and at the same time so gently and lovingly human, it is almost impossible to reconcile the two. Barry does it.

Loose Strife is in this case - the endless battle we all endure in trying to become humane. Quan Barry is quite simply masterful.

Loose Strife

Listen closely as I sing this. The man standing at the gate

tottering on his remaining limb is a kind of metronome, his one

leg planted firmly on the earth. Yes, I have made him beautiful

because I aim to lay all my cards on the table. In the book review

the critic writes, "Barry seeks not to judge but to understand."

Did she want us to let her be, or does she want

to be there walking the grounds of the old prison on the hill

of the poison tree where comparatively a paltry twenty thousand

died? In the first room with the blown up

black-and-white of a human body gone abstract someone has

to turn and face the wall not because of the human pain

represented in the photo but because of her calmness.

the tranquility with which she tells us that her father

and her sister and her brother were killed. In graduate school

a whole workshop devoted to an image of a woman with bleach

thrown in the face and the question of whether or not

the author could write, "The full moon sat in the window

like a calcified eye, the woman's face aglow with a knowingness."

I felt it come over me and I couldn't stop. I tried to pull myself

together and I couldn't. They were children. An army of child

soldiers. In the room papered with photos of the Khmer Rouge

picture after picture of teenagers, children whose parents

were killed so that they would be left alone in the world

to do the grisly work that precedes paradise.

And the photos of the victims, the woman holding her newborn

in her arms as her head is positioned in a vise, in this case

the vise an instrument not of torture

but of documentation, the head held still as the camera captures

the image, the thing linking all their faces, the abject fear

and total hopelessness as exists

in only a handful of places in the history of the visible world.

For three $US per person she will guide you through what was

Tuol Sleng prison, hill of the strychnine tree.

Without any affectation she will tell you the story of how

her father and her sister and her brother went among

the two million dead. There are seventy-four forms

of poetry in this country and each one is still meant to be sung.

...

Don't need me.

In the Semitic light I mistook

him for the gardener,

something in the look

of his hands. Give me the body,

I cried. I am of his flock.

Believe me.

The email claims I am a lady

who is very much at the top of

her game.

Now if only I lived in

Milwaukee, city of hops.

A reprieve for me.

That a woman's touch would

soil him. The white robe forever

marred. So

much of what he preached I

still don't understand

Sister, how it grieves me.

In my fantasies I imagine a

dark man in a three thousand

dollar suit,

the man a heart surgeon with a

love of poetry. Yeah yeah.

It's beneath me.

When the world ends I will

remember bits & pieces of my

wicked ways. The seven demons

of the head. The sound of our

moans when one of them

pleased me.

& tell the others I am risen

Then he points away from

himself & out into the

stony world, I imagine his heart

beating stay but his face says

leave me.

In that movie with the teen

prostitute, how no one ever

touched her yet

the maniac took up a gun. So

many ways to touch someone.

Naive me.

& what of it? A man nailed like

a bloody flag to two pieces of

wood.

the duality of the word cleave.

I get it now. He was trying

to free me.

I don't know it yet but it's good

advice. I should write it down

somewhere.

Star of the sea & the sea a sea of

bitterness. Lord God,

don't deceive me.

...

Barry does not hesitate to dance into the darkness where others fear to tread. With chops like these she can do whatever she likes and thank you, thank you, thank you.

Reading Quan Barry for the first time makes me think of my younger self, makes me remember the first time I read Michael Ondaatje, Charles Bukowski, Kurt Vonnegut. I remember those books, where I was at the time, and I know I am going to remember reading Barry forever.

These poems have heart and are heartlessly blunt. These blunt poems have beauty in spite of the bloody wounds they sever open.

Loose Strife

Everyone dreams of being harmed. It's easy. If I were to restructure the narrative,

I would start with the serial killer taking his wife's face in his hands

and nodding sagely toward the raggedy young woman by the diner door,

a baby slung on her hip. "They're the invisible ones," the killer tells his wife

who thirty years later tells the journalist who once lived as a teenage runaway

hopping from rig to rig. I have never had to force myself to stay awake

as the journalist did as she hitched cross-country. I have never had

to adopt extreme behaviors in order to stay alive. But once I needed help

and every single person who drove by pretended they couldn't see me,

ostensibly me a dirty black woman in an oversized coat

standing by the ATM. In the article the journalist details

the night a trucker pulled a knife on her then told her to run

then a different night when a woman's mangled body was found

in a truck-stop dumpster as the cab the journalist was riding in

sat filling up, all over the landscape the young runaways tortured

and killed, pierced with metal, their bodies completely shaved.

So many ways to be invisible, so many ways to be erased.

On the traffic island by the westside Target a man with his cardboard sign

saying any little thing will help. Everyone dreams of being harmed.

Much tougher to recover from the dream of harming...

The other time I went invisible I went invisible for six whole weeks.

It was November. I stood as my hands slowly froze, the whole world passing me by

even as I started crying. After 9/11 a friend joked that a black man

in a UPS uniform and a truck could still go anywhere he pleased.

Tonight if I could go anywhere I would go back to that afternoon

when the last photo of her was taken. She's so young, her body a sapling

her smile goofy and adolescent, self-conscious. She is sitting in the backseat

of a car, this murdered girl, the one he tortured for weeks in the back of his trailer,

stringing her up by a series of hooks before finally garroting her with bailing wire.

In the photo, I imagine she is on her way toward a body of water.

Something that will bear her up. In ancient Greek there is a noun for the blessing

of children. EUTEKVIA. Lord, have mercy on us. She is fourteen years old.

...

These poems have power, magic and grace. Hard to beat those three.

Quan Barry is spectacular, seriously. These poems move us all one step closer to a better understanding of what it is to be human beans.

Reading these poems makes you feel smarter.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Quan Barry is the author of three previous poetry collections: Asylum, winner of the Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize; Controvertibles; and Water Puppets, winner of the Donald Hall Prize in Poetry. She is also the author of the novel She Weeps Each Time You’re Born. Barry has received two fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts in both poetry and fiction. She is professor of English at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

BLURBS

“Violence across history, from Greek myth to modern American serial killers and the Cambodian genocide, animates this disturbing and graphically original fourth effort from Barry (Asylum). She utilizes dual-justified and unusually arrayed text to fit stark scenes where we find someone ‘hiding in a space meant/ for buckets and rags as// next door the soldiers/ drag away a young boy,’ or, in a modified ghazal, a witness at Golgotha watching ‘a man nailed like/ a bloody flag to two pieces of/ wood.’ Taking in ecological as well as human horror, falling gingko pods remind Barry of failing satellites, ‘all of which some day will come tumbling back.’ In a series of poems that belong together despite their diverse scenes, she tries ‘to describe the unimaginable/ in a time and a place when sadly everything is imaginable.’ Those vivid pictures, and their self-consciousness about what it means to narrate extremities, perhaps benefit from the book's origin in a collaboration between Barry and visual artist Michael Velliquette. And yet the book stands up, and stands out, on its own. Barry risks the lurid, and the knowing, but comes out more like a prophet, overwhelmed-sometimes sublimely so-by the first- and second-hand truths she must convey.”

and her sister and her brother were killed. In graduate school

a whole workshop devoted to an image of a woman with bleach

thrown in the face and the question of whether or not

the author could write, "The full moon sat in the window

like a calcified eye, the woman's face aglow with a knowingness."

I felt it come over me and I couldn't stop. I tried to pull myself

together and I couldn't. They were children. An army of child

soldiers. In the room papered with photos of the Khmer Rouge

picture after picture of teenagers, children whose parents

were killed so that they would be left alone in the world

to do the grisly work that precedes paradise.

And the photos of the victims, the woman holding her newborn

in her arms as her head is positioned in a vise, in this case

the vise an instrument not of torture

but of documentation, the head held still as the camera captures

the image, the thing linking all their faces, the abject fear

and total hopelessness as exists

in only a handful of places in the history of the visible world.

For three $US per person she will guide you through what was

Tuol Sleng prison, hill of the strychnine tree.

Without any affectation she will tell you the story of how

her father and her sister and her brother went among

the two million dead. There are seventy-four forms

of poetry in this country and each one is still meant to be sung.

...

PLEASE NOTE, TBOP was unable to reproduce Quan Barry's poems exactly as they appear in her book. We apologize profusely to both Ms. Barry and to the University of Pittsburgh Press. We here at TBOP will continue to try to improve our technical proficiencies. A thousand monkeys, a thousand typewriters.

...

Perhaps a word about style. Today's book of poetry has no clue why Barry has chosen a variety of formal constructs for her poems. These deliberate forms are consistent blocks, columns of text with perfect margins down both sides. I'm sure it means something and I assure you there isn't a comma out of place in these panoramic puzzles. But I don't know what it means and don't really care. Why would I? Loose Strife is a solid as it gets, Quan Barry is a stone cold heavyweight. Period.

How is it possible that one person knows what Quan Barry knows? Who can know this? How is it possible that Quan Barry riffs across the water as though she were the Siren of Time.

Do you get the idea that TBOP likes this absolutely stunning book? Loose Strife compels you to turn the page.

Noli Me Tangere

& I cried out in Aramaic, the

tongue of the only god, Rabbi,

it's me!

Noli me tangere, he whispered,

& the world went black.

Don't cleave to me.

Comfort me with apples is a

mistranslation. What the J-

writer meant:

Sustain me with raisins. Put

down a bedding of apricots.

Sleep with me.

The last time we spoke on the

phone one final moment of

connection.

Take care, he said, but I knew

what he was really saying.Don't need me.

In the Semitic light I mistook

him for the gardener,

something in the look

of his hands. Give me the body,

I cried. I am of his flock.

Believe me.

The email claims I am a lady

who is very much at the top of

her game.

Now if only I lived in

Milwaukee, city of hops.

A reprieve for me.

That a woman's touch would

soil him. The white robe forever

marred. So

much of what he preached I

still don't understand

Sister, how it grieves me.

In my fantasies I imagine a

dark man in a three thousand

dollar suit,

the man a heart surgeon with a

love of poetry. Yeah yeah.

It's beneath me.

When the world ends I will

remember bits & pieces of my

wicked ways. The seven demons

of the head. The sound of our

moans when one of them

pleased me.

& tell the others I am risen

Then he points away from

himself & out into the

stony world, I imagine his heart

beating stay but his face says

leave me.

In that movie with the teen

prostitute, how no one ever

touched her yet

the maniac took up a gun. So

many ways to touch someone.

Naive me.

& what of it? A man nailed like

a bloody flag to two pieces of

wood.

the duality of the word cleave.

I get it now. He was trying

to free me.

I don't know it yet but it's good

advice. I should write it down

somewhere.

Star of the sea & the sea a sea of

bitterness. Lord God,

don't deceive me.

...

Barry does not hesitate to dance into the darkness where others fear to tread. With chops like these she can do whatever she likes and thank you, thank you, thank you.

Reading Quan Barry for the first time makes me think of my younger self, makes me remember the first time I read Michael Ondaatje, Charles Bukowski, Kurt Vonnegut. I remember those books, where I was at the time, and I know I am going to remember reading Barry forever.

These poems have heart and are heartlessly blunt. These blunt poems have beauty in spite of the bloody wounds they sever open.

Loose Strife

Everyone dreams of being harmed. It's easy. If I were to restructure the narrative,

I would start with the serial killer taking his wife's face in his hands

and nodding sagely toward the raggedy young woman by the diner door,

a baby slung on her hip. "They're the invisible ones," the killer tells his wife

who thirty years later tells the journalist who once lived as a teenage runaway

hopping from rig to rig. I have never had to force myself to stay awake

as the journalist did as she hitched cross-country. I have never had

to adopt extreme behaviors in order to stay alive. But once I needed help

and every single person who drove by pretended they couldn't see me,

ostensibly me a dirty black woman in an oversized coat

standing by the ATM. In the article the journalist details

the night a trucker pulled a knife on her then told her to run

then a different night when a woman's mangled body was found

in a truck-stop dumpster as the cab the journalist was riding in

sat filling up, all over the landscape the young runaways tortured

and killed, pierced with metal, their bodies completely shaved.

So many ways to be invisible, so many ways to be erased.

On the traffic island by the westside Target a man with his cardboard sign

saying any little thing will help. Everyone dreams of being harmed.

Much tougher to recover from the dream of harming...

The other time I went invisible I went invisible for six whole weeks.

It was November. I stood as my hands slowly froze, the whole world passing me by

even as I started crying. After 9/11 a friend joked that a black man

in a UPS uniform and a truck could still go anywhere he pleased.

Tonight if I could go anywhere I would go back to that afternoon

when the last photo of her was taken. She's so young, her body a sapling

her smile goofy and adolescent, self-conscious. She is sitting in the backseat

of a car, this murdered girl, the one he tortured for weeks in the back of his trailer,

stringing her up by a series of hooks before finally garroting her with bailing wire.

In the photo, I imagine she is on her way toward a body of water.

Something that will bear her up. In ancient Greek there is a noun for the blessing

of children. EUTEKVIA. Lord, have mercy on us. She is fourteen years old.

...

These poems have power, magic and grace. Hard to beat those three.

Quan Barry is spectacular, seriously. These poems move us all one step closer to a better understanding of what it is to be human beans.

Reading these poems makes you feel smarter.

***

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Quan Barry is the author of three previous poetry collections: Asylum, winner of the Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize; Controvertibles; and Water Puppets, winner of the Donald Hall Prize in Poetry. She is also the author of the novel She Weeps Each Time You’re Born. Barry has received two fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts in both poetry and fiction. She is professor of English at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

BLURBS

“Violence across history, from Greek myth to modern American serial killers and the Cambodian genocide, animates this disturbing and graphically original fourth effort from Barry (Asylum). She utilizes dual-justified and unusually arrayed text to fit stark scenes where we find someone ‘hiding in a space meant/ for buckets and rags as// next door the soldiers/ drag away a young boy,’ or, in a modified ghazal, a witness at Golgotha watching ‘a man nailed like/ a bloody flag to two pieces of/ wood.’ Taking in ecological as well as human horror, falling gingko pods remind Barry of failing satellites, ‘all of which some day will come tumbling back.’ In a series of poems that belong together despite their diverse scenes, she tries ‘to describe the unimaginable/ in a time and a place when sadly everything is imaginable.’ Those vivid pictures, and their self-consciousness about what it means to narrate extremities, perhaps benefit from the book's origin in a collaboration between Barry and visual artist Michael Velliquette. And yet the book stands up, and stands out, on its own. Barry risks the lurid, and the knowing, but comes out more like a prophet, overwhelmed-sometimes sublimely so-by the first- and second-hand truths she must convey.”

--Publishers Weekly (starred review)

365

Poems cited here are assumed to be under copyright by the poet and/or publisher. They are shown here for publicity and review purposes. For any other kind of re-use of these poems, please contact the listed publishers for permission.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.