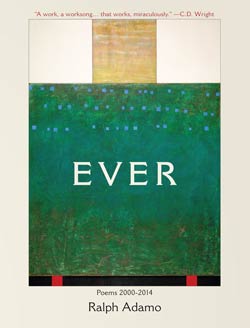

Ever - Poems 2000-2014. Ralph Adamo. Lavender Ink. New Orleans, Louisiana. 2014.

Ralph Adamo talks a damned good line in Ever. His long prose-poem "Solecisms" starts with this hammer throw:

"Although we have no right to hurt one another this poem yanks you out of your chair with

one hand and slaps you silly with the other all the while saying see it didn't have to come to

this we could have chosen justice over property, the heart's idea of what's right over the idea

formed when two heads or more get together and make a plan."

He says it right out loud, we don't mean to hurt one another but we do anyway. Adams tackles all the big subjects with vigour. These poems are searching for more understanding, more humanity.

Epilogical

The ruined body excites the ruined mind.

Or anyway that's today's de(layed) construction

of an old ache in which the bent form struggles

to reveal its cancelations (or conceal its

revelations), I'm all in, twisted to the core the other

being inglory, a retching from the center of my earth.

I dive divine into the end of things she dis-

plays, lewd an anterior lead is all, and then--

oh, I am over god, except for sentiment.

Begin again where things once thought

now rattle...you learn to tell yourself

be quiet, especially when you are

screaming...bad listener, you, hearing

it all. The form relays herself.

Each dying day recombines, a

light, breeze, you whom I am granted,

I'd break this face wide open if I could.

...

Today's book of poetry is fairly certain that Ever is Adamo opening up his rather rich veins in an attempt to understand war, wonder and the weary weight the world bestows on hope.

Adamo's poems have weight, literally, the books feels heavy and dense in your hands. The poems are easy to enter but hard to leave. His voice in these poems is always considered but never pompous enough to pretend to be clairvoyant. Adamo is strong enough to pose questions without necessarily having any answer. Adamo is searching for more, let us say that he is searching for the truth.

The Forgetting

The forgetting is ferocious and takes

all my time. In the whatevereth year

this is time stands me up as always

with a kick to the groin, as if I'd

made this plan in the beginning:

be lost in fullness, found without--

The words I carry now are so heavy

I fear that I will fall down and -- boom!--

will disappear, my moods in wild disorder

staring at the old goddamned moon again an equal--

forty years I had not read her inscription.

What was I waiting for?

Joy surprises the way love incorporates

there it is -- two colors muting, the sounding

interior shade, the loosened lip, shred

of the lost world the dream wakes up in.

Suffused in a glow of pre-happines,

I read my friend's book in bed, and

one night woke to a sky-full of geese honking

for the long time of being startled, then

amazed. You ask me even now I'll

admit I was worried, afraid, dread layered

on the ecstatic idea of happiness sus-

tained my new routines, but my heart

hurt deep in my chest, for real,

so I could feel each breath for weeks.

I wouldn't know how to live here

in a country like this where the sky

is everywhere like a flute below ground

unholy ticking, sharp sigh moistening,

stared down by an infant in a bakery,

I wonder where the string ends, my

luminous luck soft-headed as a teddy.

I throw up my hands light dripping,

a hundred books later, and after,

the song delight designed away again,

wanting to come to, wanting an end

to, coming to want for the love of it.

***

When S died I was beside myself

grieving, amazed, bereft, untouched.

When is it one learns to be careful?

almost from the first and never.

***

and now I've started repeating the names of the dead

to myself, in my mind, over and again, I think so

I won't forget which ones are dead and that they are,

not always starting from any beginning or with the same

name, but always a name -- the new ones sometimes first, so

Dusty, but then Russ, and Mary my own sister and Susan...

Robert who was crazy, Bob Woolf, imagined speaking

in my memory of him, Russ too, speaking, not Bob (Robert, in

this confusion of Bobs) who comes to me gazing,

a little wildly, as if in fatal knowledge sworn to

secrecy, Susan not speaking but always with a start somewhere deeper --

oh I haven't run out of them just sometimes they

repeat -- Maxine, and her Joe, wise from having had to let go

so long before, a young soldier in a giant war outliving, outliving

-- and so it is sometimes I know there's one I'm not recalling,

not the past -- Frank, or my father (Joe too, Joseph, whose people called

him Joey), go back too far and the other side of death appears, so

maybe I repeat and recall to keep the bloom clear death stalks...

did I forget yet, Everette whom all call Rette? who else

out there needs is or her name called? I am on duty until...

Brian! I forgot you! Others, speak --

***

We've all seen through everything by now haven't we?

Love, certainly, no matter how the residue stings. Death

we'd like to think, But work! oh, especially that --

I was startled thirty years ago to hear my father

on his deathbed, say -- a mix of irritation & awe here--

you and your friends, too smart to work...

***

still possible to overwhelm the odds

with oddities he thinks

***

The freight on waiting's heavy

The wait's a stretch, too long

to keep the garden thriving,

fish and fuel and song

arrival and depart(ure)

domestic to denature

such waiting wears a ring

fire can't climb, lives within

an estuary broken on a levee.

***

We have no way of explaining death, do we,

no protection from it, we who have understood

god's place as a romantic figure from

a foregone age -- no one to whom to drag

our broken bodies, no place to lie still

and wait --

...

Searching for the truth is one hard ask. Adamo is searching for more and that may be the most admirable reason to write poems.

Nancy Lemann, the author of Lives of the Saints had this to say about Ralph Adamo's Ever:

"Reading Ralph Adamo's poetry puts you in a country brooding world where the

truth comes driving through the gloom like elegance."

Like she said.

Pluralities

I hate that you are on the other side this evening

If I go somewhere to cry for you how will I stop

I hope this finds you well, It's been too long,

I typed when you were already gone.

Listening to you talk

over there is like

listening to water

I compose

you are here

music breaking whitely

one track crossing over another

to reach disaster

Shooed from the blues I stand

against one breeze

and feel the summer's cascade

buggy and wet in my blood

I a sunken man with an old nose and long eyes

wind-shredded

used to the way little becomes less

unprepared for bounty

whittling sorrow down to its toothsome size

***

The little house of my dead first wife

blows me a kiss as I go past

on wheels, the sidewalk cracks

one more lame joke to boot, and

then I am on the other side, again.

...

Sometimes Today's book of poetry has the best job in the world and sometimes it is the saddest. Reading Ralph Adamo's Ever is a visit to a sage uncle who has seen more of the world than you.

The answers aren't necessarily his domain, but oh, he asks a lovely question, muses with saintly illumination.

Ralph Adamo

Photo: Camille Bullock

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

A lifelong resident of New Orleans, Ralph Adamo has published six collections of poetry, most recently Waterblind: New and Selected Poems from Portals Press (2002). His book Sadness At the Private University was among the first six published by Lost Roads Publishers in 1977; his book-length poem Desire, Death, All of Them (formerly titled The Bicameralization) is seeking a publisher. Adamo edited New Orleans Review at Loyola University for most of the 90s; he teaches at LSU and Tulane Universities and at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts Academy. He and his wife Kay have a two-year old son, Jack, and an infant daughter, Lily. - See more at: http://arts.gov/writers-corner/bio/ralph-adamo#thash.CmbITq3c.dpuf

BLURBS

An I relays the story in its not-story way. With traces of story. The sound is uniquely of its city in a nearly, not-named way. Attuned to its humidfied breezes and the fan blade’s indispensable turning. Home is the sole locale, the nucleus, ever so. The voice struggles ‘to end its own noise,’ not to inventory only regrets and losses, rattled and battered; cycling through the dead, friends and kin, pictures, ‘the stalactites of memory’ and bars in which years must have passed, stumbled through, a survivor, “godly,/of one mind, learning too late whatever/was on offer, outlasting fabulous destinies…” A work, a worksong, not of an illusory life, but of a life, in a body, a family, on wheels, rubber-side down, that works, miraculously.

—C.D. Wright, author of One With Others, National Book Critics Circle Award winner.

Ralph Adamo has lived his three-score-plus years in New Orleans. To say that the poems in Ever are about that city of the dead, the dying, and the coming-to-be would be a great disservice. These are the poems of man who has become his city. To be sure, the jazz, the floods, the drunks, and the turbulence of despair are here, but they exist in the words of one who has absorbed them into himself. If “the blinked-smile the non-survivor wears / toward peace” describes one overwhelmed by it all, Adamo, ever looking forward, brings comfort, like words whispered in the ear of a drowsy child.

—R.S. (Sam) Gwynn, author of No Word of Farewell: Poems 1970-2000.

Reading Ralph Adamo’s poetry puts you in a courtly brooding world where the truth comes driving through the gloom like elegance. You picture him “standing absolutely motionless at a slight angle to the universe,” as E.M. Forster described Cavafy.

—Nancy Lemann, author of Lives of the Saints and Ritz of the Bayou.

For more than forty years, while “arguing words against / The constant threat: forgetting,” Ralph Adamo has published poems as original as any I know. In his seventh collection, Ever, in which sometimes “a word is as far from a fact / as fever can burn it,” a speaker whittles “the little lies down to / The nuance of perfect teeth in a closed mouth.” Another speaker whispers to his young children, “My children are exhausting” and “’riddle’ means ‘dark language’” in order to help spirit them to bed. In another poem, retrospection makes a speaker “sag like an old bookshelf and sigh like the door beyond it.” And in another, a speaker prays for adolescent boys in their lostness—“world without hearing, amen.” Such phrasings hint at greater recognitions to come—for instance, that poetry is “just listening to the world.” What may be most original and satisfying about the thirteen years of poems in Ever is that reading and rereading them is to experience the art and diverse craft of a master, one who would wince at the accolade and never accept it.

—Randy Bates, author of Rings: On the Life and Family of a Southern Fighter.

In Ever, Ralph Adamo has focused his poetic lens on the small moments that make life bittersweet and profound. Whether he is describing the banter of children at play or words uttered on a deathbed, Adamo puts the reader in the room and hands him a magnifying glass. The poet is asking us to watch life closely as it swiftly passes.

He gives very specific metaphors of pain, familiar to any New Orleanian “like stinging caterpillars down from ghostly cocoons en masse to prey on the bare feet of us all.” The book contains many precisely chosen words and well-considered passages. But he also offers some less concrete, more esoteric and slightly sardonic observations “Some things have always fallen through time and space to land god knows where.”

Adamo writes confidently about the value in dysfunction and skeptically about pure redemption. “I was going to get older someday. I was going to blame somebody.” Sometimes the work seems so personal that it should be reworked in the reader’s mind. In “Visiting the Marker, After the Flood,” the narrator asks “What did you expect to happen clawing through the chicken wire at the top of the 20th century.” To understand this poem about death and life, the reader must step back and watch the words flow past.

Adamo’s narrator laments the people who have disappeared without ceremony. He names them in a list broken by undisguised feelings – among them that he cannot properly remember all the names. But the spirits of the dead emerge and disappear throughout the book, allowing readers the experience of tangible and fleeting memories too.

Written in dense beautiful language, Ever is about temporal, conscious and self-conscious experiences. UnderlyingEver is a question of whether we will find the perfect afterlife. This is a book without any neat, simple answers. Still, Adamo seems to be telling us that happily ever after, our Ever, is here.

—Fatima Shaik, author of Melitte and On Mardi Gras Day.

Ralph Adamo has lived his three-score-plus years in New Orleans. To say that the poems in Ever are about that city of the dead, the dying, and the coming-to-be would be a great disservice. These are the poems of man who has become his city. To be sure, the jazz, the floods, the drunks, and the turbulence of despair are here, but they exist in the words of one who has absorbed them into himself. If “the blinked-smile the non-survivor wears / toward peace” describes one overwhelmed by it all, Adamo, ever looking forward, brings comfort, like words whispered in the ear of a drowsy child.

—R.S. (Sam) Gwynn, author of No Word of Farewell: Poems 1970-2000.

Reading Ralph Adamo’s poetry puts you in a courtly brooding world where the truth comes driving through the gloom like elegance. You picture him “standing absolutely motionless at a slight angle to the universe,” as E.M. Forster described Cavafy.

—Nancy Lemann, author of Lives of the Saints and Ritz of the Bayou.

For more than forty years, while “arguing words against / The constant threat: forgetting,” Ralph Adamo has published poems as original as any I know. In his seventh collection, Ever, in which sometimes “a word is as far from a fact / as fever can burn it,” a speaker whittles “the little lies down to / The nuance of perfect teeth in a closed mouth.” Another speaker whispers to his young children, “My children are exhausting” and “’riddle’ means ‘dark language’” in order to help spirit them to bed. In another poem, retrospection makes a speaker “sag like an old bookshelf and sigh like the door beyond it.” And in another, a speaker prays for adolescent boys in their lostness—“world without hearing, amen.” Such phrasings hint at greater recognitions to come—for instance, that poetry is “just listening to the world.” What may be most original and satisfying about the thirteen years of poems in Ever is that reading and rereading them is to experience the art and diverse craft of a master, one who would wince at the accolade and never accept it.

—Randy Bates, author of Rings: On the Life and Family of a Southern Fighter.

In Ever, Ralph Adamo has focused his poetic lens on the small moments that make life bittersweet and profound. Whether he is describing the banter of children at play or words uttered on a deathbed, Adamo puts the reader in the room and hands him a magnifying glass. The poet is asking us to watch life closely as it swiftly passes.

He gives very specific metaphors of pain, familiar to any New Orleanian “like stinging caterpillars down from ghostly cocoons en masse to prey on the bare feet of us all.” The book contains many precisely chosen words and well-considered passages. But he also offers some less concrete, more esoteric and slightly sardonic observations “Some things have always fallen through time and space to land god knows where.”

Adamo writes confidently about the value in dysfunction and skeptically about pure redemption. “I was going to get older someday. I was going to blame somebody.” Sometimes the work seems so personal that it should be reworked in the reader’s mind. In “Visiting the Marker, After the Flood,” the narrator asks “What did you expect to happen clawing through the chicken wire at the top of the 20th century.” To understand this poem about death and life, the reader must step back and watch the words flow past.

Adamo’s narrator laments the people who have disappeared without ceremony. He names them in a list broken by undisguised feelings – among them that he cannot properly remember all the names. But the spirits of the dead emerge and disappear throughout the book, allowing readers the experience of tangible and fleeting memories too.

Written in dense beautiful language, Ever is about temporal, conscious and self-conscious experiences. UnderlyingEver is a question of whether we will find the perfect afterlife. This is a book without any neat, simple answers. Still, Adamo seems to be telling us that happily ever after, our Ever, is here.

—Fatima Shaik, author of Melitte and On Mardi Gras Day.

373

DISCLAIMERS

Poems cited here are assumed to be under copyright by the poet and/or publisher. They are shown here for publicity and review purposes. For any other kind of re-use of these poems, please contact the listed publishers for permission.

We here at TBOP are technically deficient and rely on our bashful Milo to fix everything. We received notice from Google that we were using "cookies"

and that for our readers in Europe there had to be notification of the use of those "cookies. Please be aware that TBOP may employ the use of some "cookies" (whatever they are) and you should take that into consideration.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.