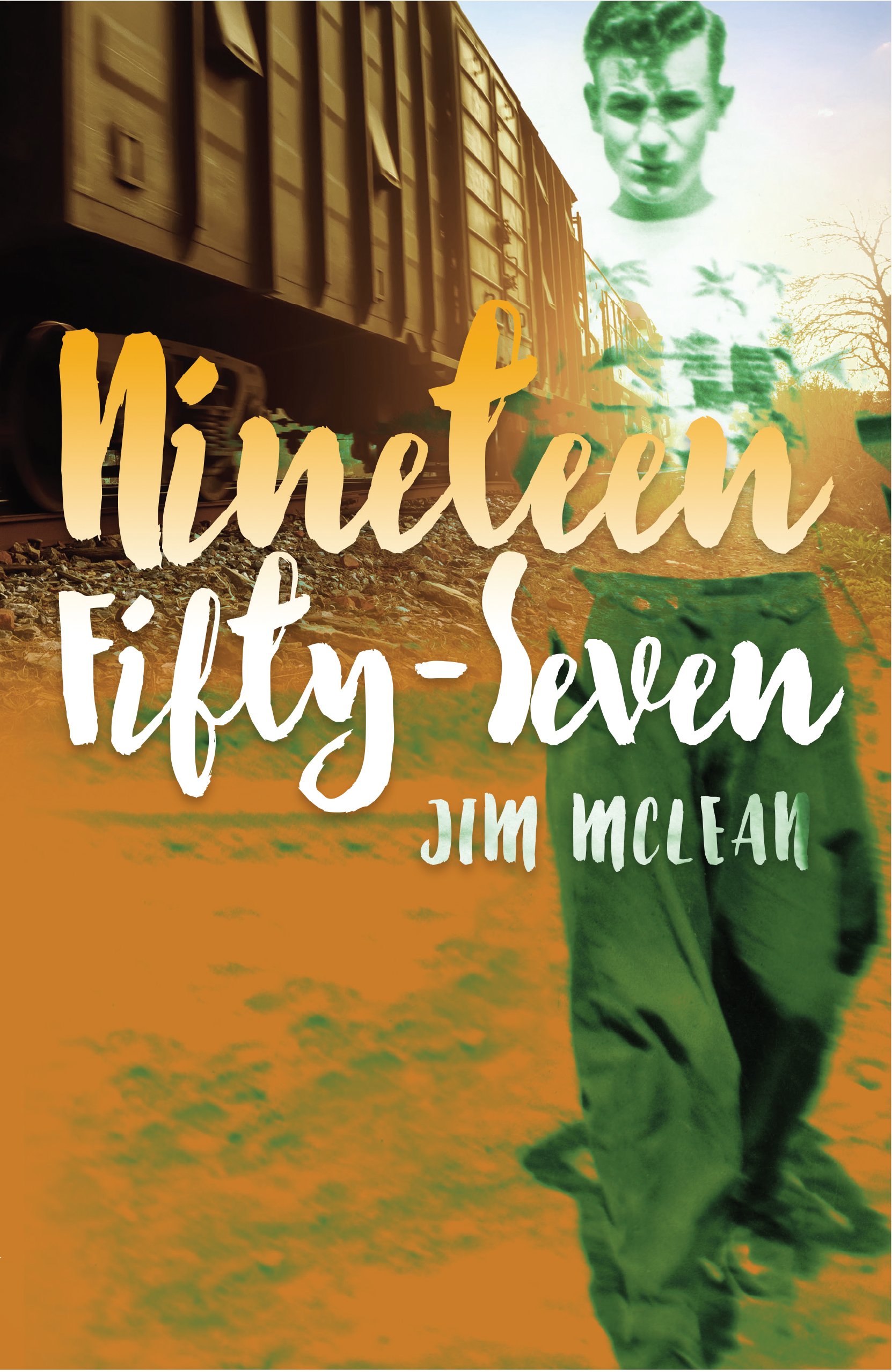

Nineteen Fifty-Seven. Jim McLean. Coteau Books. Regina, Saskatchewan. 2016.

Jim McLean isn't about to concede an inch to fashion. Nineteen Fifty-Seven reads like someone stepped on a very articulate cat's tail. This is tough-guy caterwauling of the highest order. McLean isn't in a bad mood in every poem but there is a Joe Btfsplk at the corner of every page and a devil on his shoulder.

These poems are train yard secrets, hobo's taunts and Moose Jaw lullabies. McLean has some serious narrative gifts and these poems let him show it. McLean's Nineteen Fifty-Seven is packed to the rafters with salty wisdom.

Heartbreak Hotel

R. Smith & Sons contracted for the railway,

feeding the gangs of men who came each spring

from the unemployment lines and the jails

and the reserves and the soup kitchens and River Street

to lay steel in the raw early mornings with their pitiable

shabby suit coats and soft, mushy shoes,

a few with caps.

The foremen were tough and seasoned and had to be,

it was still, back then, a long journey

from Moose Jaw to Chaplin, Old Jim,

the cook, was ex-army, 77 years old, his muscle

turned soft, turned to fat, he used to say with regret.

Up at five every morning, first thing he taught me

was not to lean my elbows on the wash stand

when I scrubbed my face in the early dawn.

It was a military thing, I guess, and he would grunt

with satisfaction to see me bend at the waist,

elbows up, over the enameled basin.

It was easy for me to give him that.

He was a pretty good old guy, Polish,

he said he was. He watched, let you show him

what you were made of.

Bill was just about as old as the cook,

skinny as a rail, with a wife at home.

No business being there,

except he needed the money, I guess.

We'd peel potatoes together every morning

for the noon meal and again in the afternoon

to get ready for supper, and talk a bit.

We'd eat our meal after the men

had gone back to the track

or to their bunks at the end of the working day

and Bill would always eat too much,

as if he was trying to store it up,

yet he never put on any weight, he'd just

get sick and then be sorry.

Bill treated me all right

and I liked him but I never wanted

to get that old and be that poor. It was 1956

and I was a kid and on my own out there.

The cook liked the way I could carry whole sides

of beef, his own strength gone,

and he gave me lots of other things to do

but my main job was to wash dishes

I washed those dishes from the meals of those hundred

or more men three times a day

with water hauled from the tender and heated

boiling hot on the stove and I sang

alone, away from everybody, at the top of my lungs

with my hands in the soapy water up to my elbows

every song I knew, Hank Snow and Williams

The Platters and Webb Pierce and I can't remember them all

and, of course, Heartbreak Hotel, by that new guy,

that I played every day on the juke-box

in the Chaplin Cafe beside the tracks when I bought a Coke

and sat on a stool like teen-agers you would see

on television and learned all the words for singing later

away from everybody

...

Any poet who hearkens the spirits of William Faulkner, Robert Penn Warren and Charles Bukowski is going to get a piece of my time. Throw in an entirely sweet 80th birthday ode to the King, Elvis Aaron Presley and Today's book of poetry is a your new fan.

Jim McLean travels back and forth in time with these poems, we see him as a young man and earning the regrets he'll carry later and then full circle we hear the mature older man's wisdom. McLean's hero carries some heavy water in these poems but there are no "woe is me" moments. McLean is old school all the way.

My Brother, Who I Looked Out for

When We Were Kids

it was the tenth or the fiftieth

or the hundredth time

we brought him to the house

and called his sponsor who didn't even want

to bother with him any more he said

he just want to kill himself, there's nothing

you can do

and it was true, he looked like death, his skin

translucent, waxy I said

you've got to get straight, get a job

and he laid there on the couch and said

I can't work out in the cold

I need an office job, an executive job

and that was bad, because I knew then

how hopeless things were

and he promised, for the hundredth time

to stop drinking and to go to the meetings

and we piled groceries into bags

and I drove him to the place where he lived

Wong said he owed last month's rent

and I paid that and the next month in advance

and I made him give me a receipt

he sold the groceries

because somebody saw him an hour later on the street

with his woman and said

by the way they were falling down

they must have got hold of something

it was a thing to crush you

we couldn't do anything and we couldn't stop trying

finally, my father came down from the Coast

he ended up drinking with him, told us

we didn't do anything to help him

when he said that he was lucky he was my father

he bought two tickets, took him back

to Vancouver on the train

afterward he wrote a letter, saying things

hadn't worked out saying he'd been

wrong, saying he'd left and he didn't

know where he was

a long time later he wrote again telling us

about how he'd come across

a newspaper item, just a few lines

buried in a back page that said he died

alone in some flophouse and that the city

had buried him as having

no known next of kin

I wrote my father a letter, he needed something

was looking for something

from me and told him we all had tried

I said he had taken that wrong turn

and but for the grace of God

it could have been me

it was nobody's fault

...

Today's book of poetry had a good time rooting through Nineteen Fifty-Seven because Mclean doesn't really ever take his foot off of the gas. These poems pound through the gears and when you come out the other side you know you've been taken for ride. This is a robust read filled with characters you've already met, people you already know. McLean's tales are writ large and aren't afraid to stomp their feet as they march across the page.

McLean's Nineteen Fifty-Seven both convinces and reminds Today's book of poetry of just how beautifully horrible we humans can be to each other and how redemption is only a poem away.

My Father's Hat

I bought a hat, a fedora

and bent down the brim

on the front right side and trained it

with a binder clip

The first time my sister saw it she said

My God, you look just like Dad

and I looked in the mirror

and she was right

and I thought about all those

little pieces of paper he used to fill

with strange cryptic columns

of numbers and I thought about

how one day he threw everything away

his job, years of service

sold the house, moved us far away

from our school and our friends

like we were being punished for something

like he was punishing himself

It was hard at first

but we were young and resilient

and bounced back, some of us

and I learned not to blame him

or myself or the world and searched

until I found all the little pieces

and put them back together and never

threw away anything important

and I remembered, years later

stopping to visit him in Vancouver

sitting mostly silent until a decent interval

had passed, getting up, saying

I wanted to walk along English Bay

while I was here and he, surprising me

offered I'll go with you

and as we watched the tide he said

You've done all right for yourself

which is about as close as he ever came.

...

Jim McLean must be one tough old son of a B, there is some hard railroading in these poems, the toughest kind of love. It's clear McLean kissed the wrong gal once or twice and feels some sort of way about it. This is hearty, vibrant and compelling narrative poetry with a brylcreemed ducktail full of memory on the side.

No business being there,

except he needed the money, I guess.

We'd peel potatoes together every morning

for the noon meal and again in the afternoon

to get ready for supper, and talk a bit.

We'd eat our meal after the men

had gone back to the track

or to their bunks at the end of the working day

and Bill would always eat too much,

as if he was trying to store it up,

yet he never put on any weight, he'd just

get sick and then be sorry.

Bill treated me all right

and I liked him but I never wanted

to get that old and be that poor. It was 1956

and I was a kid and on my own out there.

The cook liked the way I could carry whole sides

of beef, his own strength gone,

and he gave me lots of other things to do

but my main job was to wash dishes

I washed those dishes from the meals of those hundred

or more men three times a day

with water hauled from the tender and heated

boiling hot on the stove and I sang

alone, away from everybody, at the top of my lungs

with my hands in the soapy water up to my elbows

every song I knew, Hank Snow and Williams

The Platters and Webb Pierce and I can't remember them all

and, of course, Heartbreak Hotel, by that new guy,

that I played every day on the juke-box

in the Chaplin Cafe beside the tracks when I bought a Coke

and sat on a stool like teen-agers you would see

on television and learned all the words for singing later

away from everybody

...

Any poet who hearkens the spirits of William Faulkner, Robert Penn Warren and Charles Bukowski is going to get a piece of my time. Throw in an entirely sweet 80th birthday ode to the King, Elvis Aaron Presley and Today's book of poetry is a your new fan.

Jim McLean travels back and forth in time with these poems, we see him as a young man and earning the regrets he'll carry later and then full circle we hear the mature older man's wisdom. McLean's hero carries some heavy water in these poems but there are no "woe is me" moments. McLean is old school all the way.

My Brother, Who I Looked Out for

When We Were Kids

it was the tenth or the fiftieth

or the hundredth time

we brought him to the house

and called his sponsor who didn't even want

to bother with him any more he said

he just want to kill himself, there's nothing

you can do

and it was true, he looked like death, his skin

translucent, waxy I said

you've got to get straight, get a job

and he laid there on the couch and said

I can't work out in the cold

I need an office job, an executive job

and that was bad, because I knew then

how hopeless things were

and he promised, for the hundredth time

to stop drinking and to go to the meetings

and we piled groceries into bags

and I drove him to the place where he lived

Wong said he owed last month's rent

and I paid that and the next month in advance

and I made him give me a receipt

he sold the groceries

because somebody saw him an hour later on the street

with his woman and said

by the way they were falling down

they must have got hold of something

it was a thing to crush you

we couldn't do anything and we couldn't stop trying

finally, my father came down from the Coast

he ended up drinking with him, told us

we didn't do anything to help him

when he said that he was lucky he was my father

he bought two tickets, took him back

to Vancouver on the train

afterward he wrote a letter, saying things

hadn't worked out saying he'd been

wrong, saying he'd left and he didn't

know where he was

a long time later he wrote again telling us

about how he'd come across

a newspaper item, just a few lines

buried in a back page that said he died

alone in some flophouse and that the city

had buried him as having

no known next of kin

I wrote my father a letter, he needed something

was looking for something

from me and told him we all had tried

I said he had taken that wrong turn

and but for the grace of God

it could have been me

it was nobody's fault

...

Today's book of poetry had a good time rooting through Nineteen Fifty-Seven because Mclean doesn't really ever take his foot off of the gas. These poems pound through the gears and when you come out the other side you know you've been taken for ride. This is a robust read filled with characters you've already met, people you already know. McLean's tales are writ large and aren't afraid to stomp their feet as they march across the page.

McLean's Nineteen Fifty-Seven both convinces and reminds Today's book of poetry of just how beautifully horrible we humans can be to each other and how redemption is only a poem away.

My Father's Hat

I bought a hat, a fedora

and bent down the brim

on the front right side and trained it

with a binder clip

The first time my sister saw it she said

My God, you look just like Dad

and I looked in the mirror

and she was right

and I thought about all those

little pieces of paper he used to fill

with strange cryptic columns

of numbers and I thought about

how one day he threw everything away

his job, years of service

sold the house, moved us far away

from our school and our friends

like we were being punished for something

like he was punishing himself

It was hard at first

but we were young and resilient

and bounced back, some of us

and I learned not to blame him

or myself or the world and searched

until I found all the little pieces

and put them back together and never

threw away anything important

and I remembered, years later

stopping to visit him in Vancouver

sitting mostly silent until a decent interval

had passed, getting up, saying

I wanted to walk along English Bay

while I was here and he, surprising me

offered I'll go with you

and as we watched the tide he said

You've done all right for yourself

which is about as close as he ever came.

...

Jim McLean must be one tough old son of a B, there is some hard railroading in these poems, the toughest kind of love. It's clear McLean kissed the wrong gal once or twice and feels some sort of way about it. This is hearty, vibrant and compelling narrative poetry with a brylcreemed ducktail full of memory on the side.

Jim McLean

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jim McLean had a long career with Canadian Pacific Railway and with Transport Canada, living and working in various Canadian locations. He is an original member of the Moose Jaw Movement poetry group, and his work has appeared in magazines and anthologies and on CBC Radio. He is the author of The Secret Life of Railroaders and co-author of Wildflowers Across the Prairies. His illustrations have appeared on book covers and in several literary and scientific publications.

Jim McLean

reading Elvis Agonistes

from Nineteen Fifty-Seven

video: Coteau Books

coteaubooks.com

541

DISCLAIMERS

Poems cited here are assumed to be under copyright by the poet and/or publisher. They are shown here for publicity and review purposes. For any other kind of re-use of these poems, please contact the listed publishers for permission.

We here at TBOP are technically deficient and rely on our bashful Milo to fix everything. We received notice from Google that we were using "cookies"

and that for our readers in Europe there had to be notification of the use of those "cookies. Please be aware that TBOP may employ the use of some "cookies" (whatever they are) and you should take that into consideration.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.